Gamers, trendsetters, rule followers. Those were just three of the rather obtuse categories we outlined to try to capture a truly diverse sample of students. The goal was to get 300 students of differing ages and perspectives to talk to each other and to us about a vision for the high school of the future. To do that, we needed to create a learning environment that was open, creative, critical, and fun. “Why don’t we just find 10 adults on campus who can hand out 30 tickets each.” My suggestion was met with a rather frustrated look from the deputy superintendent, David Haglund. “How could you think of anything more boring than that?” came the response. Point taken.

Visual artists, athletes, community-minded. We settled on a much more subversive plan. We would meet beforehand with 30 students from a range of grades and interests, and give each of them ten colored tickets. Each ticket represented one of our categories, and the students had 48 hours to pass out their allotment of tickets. At 9:55 on Friday, anyone with a ticket was instructed to get up and walk out of class. Wes Kriesel, our Coordinator of 21st Century Learning, was the third member of our planning team. “Are we going to tell the teachers what’s going on?” There was some back and forth discussion about minimizing disruption while encouraging a lingering buzz about what was going on. Ultimately, we tipped the staff to the 9:55 walkout, but left enough ambiguity to encourage discussion.

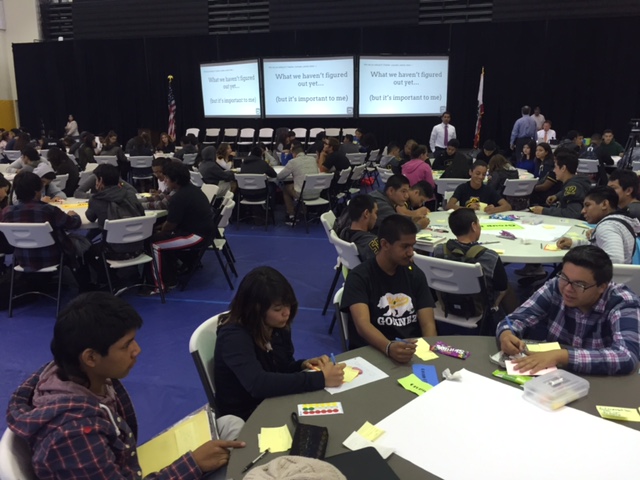

Performing artists, overachievers, rebels. It was 10 am, and students started streaming into the gym. Energy was high as the entering mass of sought out tables that matched their tickets, music pumping in the background. “What does everyone at the table have in common?” was the first question, and then students were asked to pull out their cell phones and text something unique about them up to the three giant video screens at the front of the room. Before they could settle in, students were again on their feet, this time seeking out a table with someone from each of the ten categories. They repeated a brief discussion about what they had in common and what might be unique about them. Our team of three planners had expanded to nearly a dozen adults who flowed around the room with throwable microphones that we would use to share pieces of the discussions unfolding at each table.

Then we settled in to the main activity. We put ten topics on the front screens, each topic connected to a primer video or image and a discussion question. I called the activity cool squares, but was alone in my enthusiasm for the title. Students used their phones to vote for the topics they wanted to talk about. I’m not a morning person launched us into a conversation about school schedules, while What inspires me got them talking about how high school might encourage or hinder them from focusing on their interests. Other topics were introduced by phrases like The school to prison pipeline, or Stop telling me what to do. Students reflected individually for a moment on each discussion question, and then engaged with their table mates, all the while the adults in the room tossed microphones to students as they shared their thoughts with the group.

When we got to the school to prison pipeline, an energized student called for the mic. “I don’t think you guys know enough about what this is talking about…” This young woman’s passion for the topic was clear as she stood to engage the crowd. Another student’s insight was equally powerful. “Listen, there is a difference between learning and passing a class, and sometimes it seems like the entire system just cares about passing.” Sometimes students broke into spontaneous applause. Other times tables engaged in a healthy debate, passing the mic from student to student. The discussion pulsed from cell phone voting, to primer video, to individual thinking, to small group discussion and then large group share out and then back again.

To close, each table put up five priority statements on poster paper. The walls of the gym were lined with text, and then students engaged in a gallery walk using colored stickers to help prioritize their statements. As they left the gym to head out to a BBQ lunch prepared especially for them, they each placed a post-it note on the metal gym doors, indicating the most important thing they wish the adults around them could figure out when it comes to their opportunities for learning and success.

Now we are engaged in the hard work of reviewing the data, identifying patterns, and setting priorities – not to mention engaging students in similar ways at all the high schools throughout the city. We are serious about our commitment to integrating student voice into our work and the way we think about our schools and systems. As students streamed out of the gym, one of them asked me a question that sums up our purpose and our challenge. “Are you actually going to do anything about what we’ve said?”