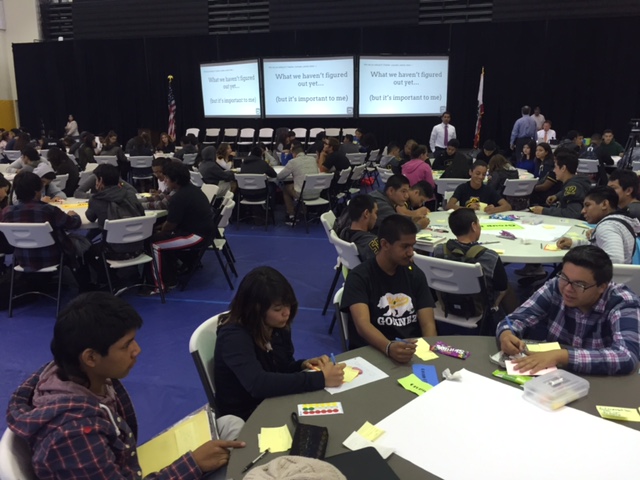

I was standing in the middle of a circle of about 50 people this morning. The circle was a mix of parents, students, teachers, counselors and administrators. We were holding our first informational meeting for our new art conservatory school in Santa Ana, and I was leading it off with a circle discussion to welcome everyone.

It was one of those moments when for a split second the vision of the work was tangible. Time slowed down as each member of the circle shared a word that described what they were hoping for in their soon-to-begin high school experience. Creativity. Equity. Opportunity. The sense of excitement and possibility was elevated as each member of the circle took a turn to contribute their word.

We’ve been working on this school redesign for over half a year. Being new to a large school district, I had no idea the degree of collaboration, strategic thinking, relationship building, and sheer will that would be required to move a project like this forward. The systems in place are designed to carry out the work the district already knows how to do – and in most cases still needs to do. 50,000 plus students need lunch every day, paychecks need to be processed, and routine maintenance of a vast set of facilities must roll forward. In that context, a small redesign project here or a new school opening there just don’t seem terribly important.

But it is deeply important.

And it is not a small task at all.

It requires the dedication and planning of teachers who already have classes to teach and programs to run. It requires the focus and attention of a site administration team that is trying to embrace and manage change while simultaneously managing a school of over 2000 students. It requires contributions from practically every department within the district, from budget analysts to facilities planners to logistics staff to curriculum specialists.

The intensity of the work is such that my small team – a team that has come together out of shared passion and not by administrative fiat – decided several weeks ago that we would need to meet every day to manage the magnitude of the work. We started to “scrum” – a term borrowed from the world of software development where development teams hold a short stand-up meeting each day to report on progress, outline priorities, and discuss obstacles. We use the Voxer app as a walkie talkie on our phones that allows us to communicate with one another throughout the day as we tackle the daily objectives we’ve set out for our team. Assignments are fluid. We pick up where someone else simply can’t fit in the task.

Before I came to Santa Ana, I had multiple friends express their skepticism that a traditional district could foster the type of innovative and forward-thinking culture that would be necessary to truly accelerate learning for all students. We still have a long way to go, and there are definitely moments of genuine frustration. Yet the appetite for true improvement is increasingly pervasive. That shared vision and commitment shows itself in unanticipated ways and in unexpected moments. It has come from a print shop manager who constantly finds a way to get materials printed on unacceptably short notice. It has come from directors who find ways to provide financial backing and classified staff who squeeze an additional task into the end of their work day. It has come from administrative supervisors who allow space for experimentation, failure, and adaptation. It has come from a Governing Board that insists on equitable access to enrichment and high quality instruction for all students.

Every so often, you get that moment when the vision just doesn’t seem that far away. As we closed our circle this morning, our arts program specialist who forms part of our small team leaned over to me and said “it’s real now, isn’t it?” Yes, indeed it is.